Lur Epelde, Briony Jones and Joe Taylor

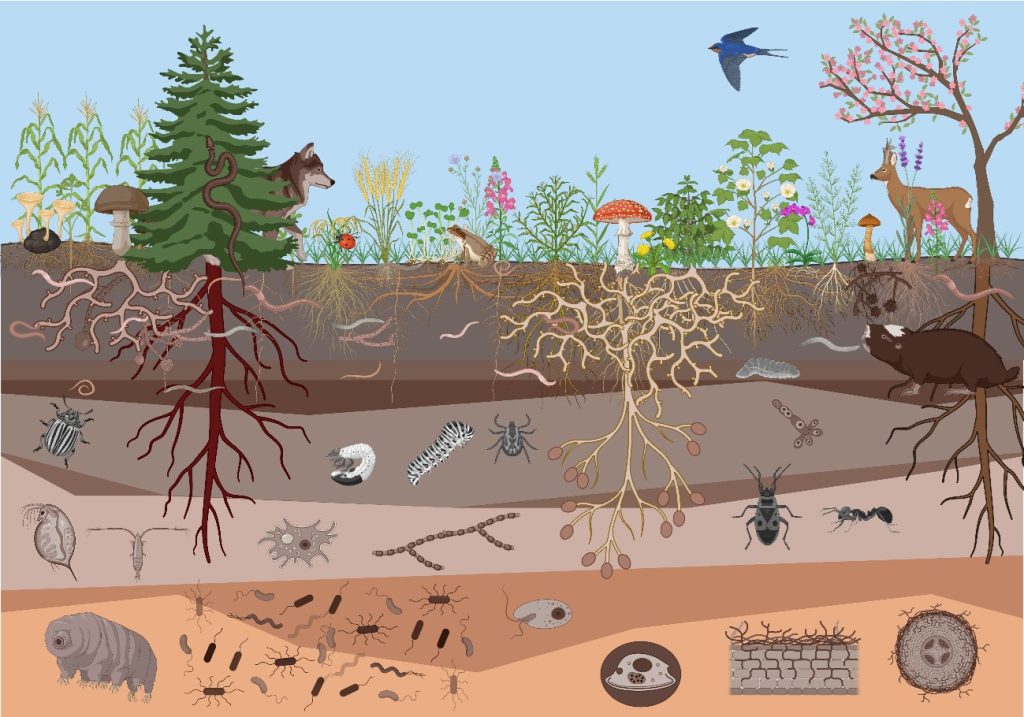

Soil is a complex ecosystem teeming with an astonishing diversity of life. A single gram of soil can contain millions of microorganisms, including viruses, bacteria, fungi, archaea, and protists, alongside microscopic animals such as nematodes and tardigrades. This immense biodiversity is more than just fascinating; it plays a fundamental role in maintaining healthy ecosystems.

Soil organisms drive key ecological functions such as nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, and plant growth promotion. Microbes break down dead plant material, recycling carbon and nitrogen back into the ecosystem. Mycorrhizal fungi form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, enhancing water and nutrient uptake. Larger organisms like earthworms contribute by aerating the soil and facilitating microbial activity. The interactions within this underground web are intricate, and disruptions—caused by pollution, land use change, or climate shifts—can have cascading effects on entire ecosystems.

Figure 1. An overview of the soil biodiversity.

Despite its importance, soil biodiversity remains one of the least understood aspects of ecology. Traditional methods of studying soil life, such as culturing microbes in a lab, capture only a small fraction of the species present. This is where analysis of DNA becomes a game-changer. By extracting and sequencing environmental DNA (eDNA) directly from soil, researchers can obtain a far more comprehensive picture of microbial and faunal communities without the need for cultivation.

The basics of the method, from soil to sequence

Environmental DNA (eDNA) is revolutionising how we study biodiversity, providing a non-invasive way to detect organisms from the genetic material they leave behind. In soil, eDNA can originate from bacteria, archaea, fungi, protists, plants, and even animals, offering a snapshot of ecosystem diversity and health. But how do we extract and analyse eDNA from something as complex as soil?

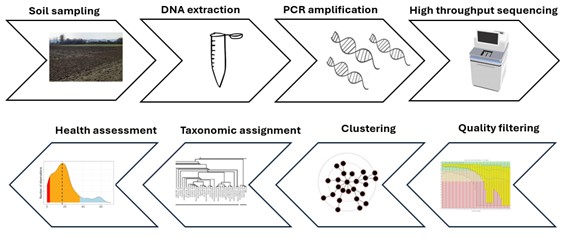

The specific method we are using in AI4SoilHealth is called amplicon sequencing or metabarcoding. The process begins with soil sampling, where researchers collect small amounts of soil from specific locations. The samples are then taken to the lab, where DNA extraction is performed using specialised kits that isolate genetic material from the mixture of organic matter, minerals and living organisms. Once the DNA is purified, it undergoes PCR amplification, a technique that targets specific genetic markers to identify different species present in the sample. This technique selects for the gene of interest and then makes millions of copies of it so it can be analysed in detail.

Next, sequencing is performed, often using high-throughput methods like the Illumina sequencing platforms. These generate massive amounts of data, which are then processed using bioinformatics pipelines to match DNA sequences against reference databases. This step reveals the species composition of the soil community, helping scientists track biodiversity changes or assess soil health.

Figure 2. Key steps in soil DNA metabarcoding.

Challenges in eDNA analysis

While eDNA is a groundbreaking tool for studying soil biodiversity, it comes with several limitations that researchers must consider. One major challenge is that eDNA provides only a snapshot in time, making it difficult to determine whether detected organisms are currently active or just remnants of past life.

Another issue is that soil is highly heterogeneous, with genetic material clumping around organic matter or being trapped in tiny pore spaces. This can lead to sampling bias, where two nearby samples yield very different results. Proper sampling strategies and replicates are crucial to overcoming this challenge.

Another limitation is the lack of complete reference databases. eDNA analysis relies on comparing sequences to known genetic data, but many soil microbes and invertebrates remain unclassified. This means that a large portion of detected DNA may not be classified taxonomically, limiting interpretation.

Addressing these limitations will be essential for refining eDNA-based soil biodiversity studies and improving our understanding of soil ecosystem functions.

Our research in AI4SoilHealth

In our project, we are addressing some of the challenges of using eDNA for soil biodiversity monitoring, working at pilot sites to assess how eDNA data varies across space and time. A key focus is comparing eDNA and eRNA metabarcoding of 16S rRNA and ITS to distinguish between total and active prokaryotic and fungal communities. Additionally, we are measuring a broad range of soil physicochemical and biological properties to identify the environmental factors influencing molecular data. Working with the datasets obtained, we aim to predict functions and construct microbial interaction networks, shedding light on the complexity of soil biology and exploring its potential as metrics for long-term soil health monitoring.

Beyond our field studies, we are scaling up our research by leveraging public data repositories to develop predictive models of soil microbial diversity. Using machine learning, we are working towards the validation of soil microbial biodiversity indicators across the EU from environmental data. These efforts will enhance our ability to predict changes in soil ecosystems under different environmental and land-use conditions.

As we refine these approaches, eDNA continues to prove its potential as a transformative tool in soil ecology. By addressing its limitations and integrating it with other methods, we move closer to a more comprehensive, scalable, and reliable way to monitor soil biodiversity. Our work contributes to building a future where soil health assessments are faster, more accurate, and accessible for both researchers and land managers, ensuring better-informed conservation and agricultural practices.